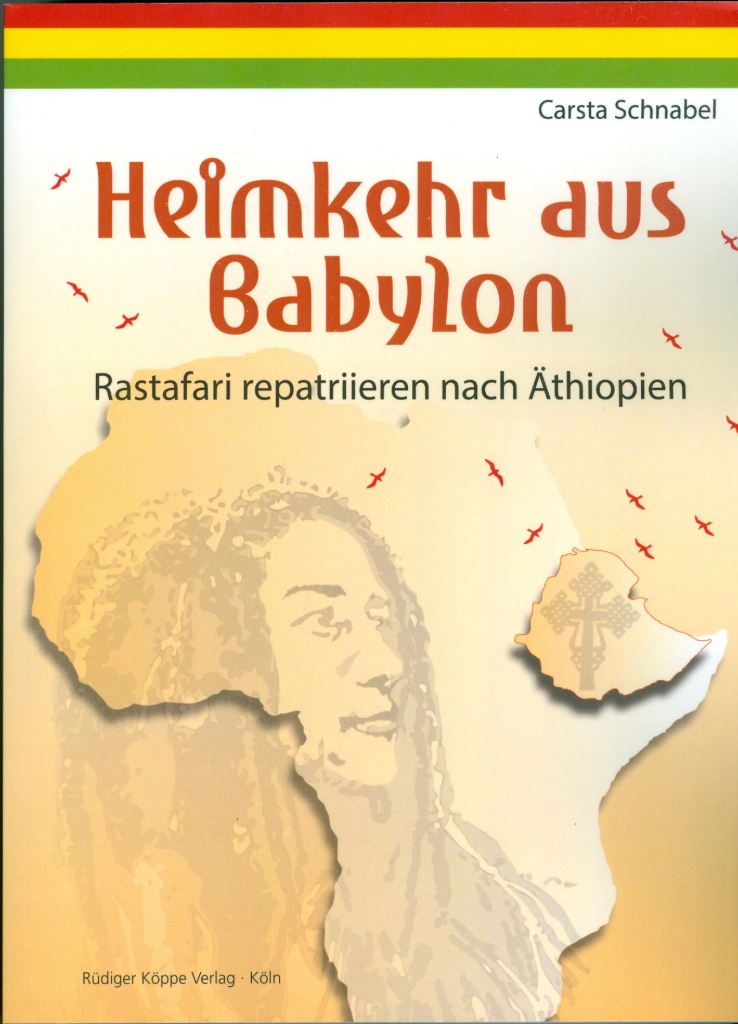

Only a small number of the men and women who refer to themselves as Rastafari are able to reach the utmost goal of this movement: Repatriation – turning away from “Babylon”, synonymous with Western culture and values, which are considered as profoundly wrong, and returning home to the land of their ancestors – to Africa. During her research visits to the international Rastafari community in Shashemene / Ethiopia the author looks into the personal living conditions under which the repatriates took up the challenge of migration. She gains insight into their current situation through intensive conversations. What was the decisive factor prompting them to turn towards Rastafari? What motivated them to return to Ethiopia? And how does it feel to finally live there?

On the basis of statements made by her informants and own observations, Carsta Schnabel characterises the social fabric of this community with its wide range of biographies, cultural backgrounds and beliefs, while also taking into account the Ethiopian perspective on the repatriates. She draws a multifaceted picture of Rastafari livity in Shashemene as well as of the surrounding Ethiopian culture and brings into focus interaction and mutual reception.

Not only does Carsta Schnabel’s account particularly leave room for a deeper insight into Rastafari, but her personal perception is also revealed – an encounter with spiritually motivated migrants in their new social environment.

Under this link you will find the full text of the review by Andrea Hollington.

Following the link at the bottom, you will find a reading sample of this exciting book.

Under these links you will find further (auto)biographical accounts of various African and non-African characters:

Schnabel’s account of her initial travels to the East African country is enriched by detailed background information on the development and history of Rastafari, together with its transnational and Biblical ties. Her in-depth descriptions of encounters with Rastafari and Ethiopians during the initial stages of her study offer insights into her personal perceptions of the environment, the individuals and the cultural and spiritual background. [...]

In conclusion, the book makes a valuable contribution to the history of repatriation to Ethiopia by focusing on bibliographical narratives and aspects of community life. While there are other publications on the Rastafari community in Shashemene (e.g. Bonacci 2010, 2015, MacLeod 2014), Schnabel’s monograph constitutes the first comprehensive account of the community in German. The book is written for a broader readership beyond academia, and will draw attention to those people who are interested in Rastafari and Reggae, Ethiopia, migration, intercultural communication, and biographies.

Andrea Hollington in Afrikanistik-Ägyptologie-Online, https://www.afrikanistik-aegyptologie-online.de/archiv/2018/4683

„A chapter a day!“ Dieses Twelve-Tribes-Motto für eine disziplinierte Bibellektüre ist auch bei „Heimkehr aus Babylon“ angebracht, denn mit 608 Seiten liegt hier ein richtig dicker Schinken vor. Doch es lohnt sich, sich durchzubeißen.

Auch wenn ihr Vorname alle Buchstaben des Wortes „Rasta“ enthält und sie eigentlich alt genug ist (Jg. 1955), um Bob Marley live erlebt zu haben, kommt die Autorin Carsta Schnabel erst spät mit dem Thema in Berührung, nämlich 2008, bei einer zufälligen Begegnung mit einer Bobo Ashanti-Gruppe auf den Seychellen. Fasziniert von diesem ersten Kontakt entschließt die promovierte Biologin und „Spät-Studentin“ der Ethnologie, für ihre Magisterarbeit die repatriierten Rastas im äthiopischen Shashemene zu interviewen.

Schnabels vorurteilsfreier Ansatz ist der Tatsache geschuldet, dass sie weder auf ideologisch-religiösen noch musikalischen Umwegen zum Thema gekommen ist, sondern wie die sprichwörtliche „Jungfrau zum Kinde“. Statt mit Bewertungsschablonen begegnet sie ihren Interviewpartnern mit aufrichtigem Interesse. Schnabel verzichtet auf die Einbettung ihrer „Feldforschung“ in einen theoretischen Rahmen und lässt stattdessen die „Informanten“ ausführlich zu Wort kommen. So entsteht eine umfangreiche Sammlung von Original-Zitaten, die die Autorin mit ihrem kulturellen und historischen Kontext verknüpft.

Nach EWF, Twelve Tribes, Nyahbinghi, Bobo und „Unabhängigen“ geordnet, werden die ca. 40 interviewten Rastas vorgestellt. Dabei kristallisieren sich Unterschiede in den Organisationsformen, Ernährungs- und Kleidungsvorschriften oder der Bedeutung von Haile Selassie und Jesus Christus heraus, die auch aus Jamaika und anderen Ländern bekannt sind. Jeder Interviewpartner trägt seinen individuellen Teil zur Geschichte des „Land Grant“ bei. Einige von ihnen, darunter der 2012 verstorbene Gladstone Robinson, gehören noch zu den „Pionieren“, die in den 1960ern und 70ern repatriierten. Auch nach dem Sturz von Haile Selassies 1974 blieben einige Rastas in Shashemene und überdauerten das sozialistische Derg-Regime. Seit dessen Ende 1991 hat Ihre Anzahl wieder zugenommen. Die aus Jamaika Repatriierten sind nach wie vor in der Mehrheit. Schnabel hat aber auch Rastas interviewt, die aus anderen karibischen Ländern, aus den USA, Europa und Neuseeland oder aus afrikanischen Ländern, wie Kenia und Südafrika, kamen – Rastas aus diversen sozialen Kontexten und Familiensituationen, darunter auch ein paar „Weiße“. Die meisten haben Probleme mit ihrem Aufenthaltsstatus und ungeklärten Landbesitzrechten. Einige sind inzwischen mit Äthiopier/innen verheiratet oder der Ethiopian Orthodox Church beigetreten. Andere distanzieren sich von der sie umgebenden Gesellschaft. Umgekehrt scheinen sehr wenige Äthiopier die Rasta-Konzeptionen wirklich zu akzeptieren, wie v.a. im letzten Teil des Buches deutlich wird, in dem sich Schnabel auf Interviews mit Äthiopiern aus dem Rasta-Umfeld konzentriert. So ist das idealisierte Äthiopien-Bild der Repatriierten kaum mit der Realität vor Ort in Einklang zu bringen, und es stellt sich die Frage, ob langfristig eine Aufgabe der Rasta-Kultur die einzige Möglichkeit ist, um sich in die äthiopische Gesellschaft zu integrieren.

An einigen Stellen hätte man das Buch übersichtlicher strukturieren und Wiederholungen und Zeitsprünge vermeiden können. Insgesamt ist es aber sehr spannend, äußerst vielschichtig, gut lesbar und unverzichtbar für alle, die sich für das Thema Repatriation interessieren.

Volker Barsch in Riddim, 2018, 94/4, 95

© 2026 by Rüdiger Köppe Verlag – www.koeppe.de