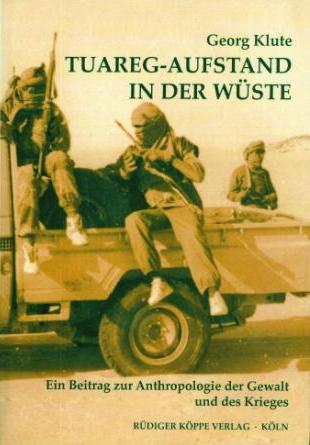

From an outsider’s point of view, the rebellions of the Tuareg may appear as hardly spectacular events – particularly in comparison to other ongoing wars in Africa. They took place in barren and remote areas of the states of Mali and Niger which are among the poorest and least known countries of the world; they did not pose a serious threat to adjacent states, let alone universal peace; they did not pique the interest of third parties so that external military interventions were held off; and they affected a comparatively small number of people.

The Tuareg rebellions are part of a series of current wars in Africa and other areas of the so called Third World which bear a close relation to the emergence and failure of the (modern) state. Just like the establishment of colonial states in Africa involved massive violence, so does the decline of the post-colonial state. Particularly the collapse of the state’s monopoly on violence and the wars resulting from it account for the diagnosis that the utopian conception of the western state model is to a large extent doomed to failure in post-colonial Africa. The fragility of many African states does not only reveal that the statal monopoly on violence is susceptible to breakdown, but also offers to ethnic groups the possibility to successfully enforce their own perceptions of social organisation, based on their tradition, against the model of the state.

The present study addresses two tasks: to contribute to both the historical investigation of the Tuareg rebellions as well as to the Social/Cultural Anthropology and Sociology of War. On the basis of the question why it is precisely the Tuareg that violently rose up and took a stand against the respective central governments of the multi-ethnic states of Mali and Niger, the author deals with three subject fields: He traces processes of ethnic identity building and differentiation among the Tuareg as well as the development of relations to neighbouring ethnic groups, then decodes the emic logic and internal justification behind the resort to violence and finally examines the relation of the Tuareg to the post-colonial state, therefrom deducing further statements about the character of statal power in this part of Africa.

******************************************************************************************************

Geleitwort (Trutz von Trotha)

Wer zukünftig über den Kleinkrieg und die oft gewaltsame Suche nach neuen politischen Ordnungen jenseits des postkolonialen Staates in Afrika nachdenken und schreiben will, wird in meinen Augen nicht an diesem Buch von Georg Klute vorbeikommen.

Der Sache nach will es einen Beitrag zur geschichtlichen Darstellung der Tuaregrebellionen bis in die späten 1990er Jahre leisten. Aber weit gefehlt! Mit sorgsamen und systematischen Schritten von der emischen zur analytischen Betrachtungsweise wird hier eine allgemeine Theorie der Gewalt vorgelegt, darunter vor allem eine des Kleinkrieges und seiner Bändigung durch politische Herrschaft. Konsequent wird auf der Prozesshaftigkeit von Gewalt und Herrschaft bestanden, und die Zerbrechlichkeit von politischer Herrschaft gegenwärtig gemacht.

Es ist ein Prozess zwischen dem Zustand der „verallgemeinerten Gewalt“, wie Georg Klute in Anlehnung an Kurt Beck sich ausdrückt und einer prekären parasouveränen Herrschaft, der es vor allem gelingen muss, die „Basislegitimität“ des Schutzes vor Gewalt für sich zu gewinnen. Während man dies als den herrschafts-soziologischen Kern der Darstellung von Klute ansehen kann, enthält die Abhandlung zahlreiche weitere wichtige theoretische Konzepte, wie eine neue Vorstellung von „ethnizistischen“ Bewegungen, „staatlicher Ethnizität“ oder der Zeit im sich wandelnden Ordnungsrahmen des Kleinkrieges. Hier wird ein methodisches Feuerwerk von solcher Originalität entzündet, wie es mir in der einschlägigen Literatur noch nicht begegnet ist.

Radikal wird mit der emischen Perspektive der Ethnologie ernst gemacht. So beginnt Klute mit der geschichtlichen Rekonstruktion der Tuaregrebellionen mit einer gründlichen und packenden Analyse der Lieder und der Poesie der Tuareg bzw. der Išumar.

Schließlich ist das Buch sicherlich auch für den Spezialisten der Tuaregrebellionen aufschlussreich. Es ist von solch einem ethnographischen Reichtum und weicht von den bisherigen Darstellungen dadurch ab, dass es transnationale Aspekte wie die Länder Niger, Algerien und Libyen ebenso wie die Thematik des Exils einschließt.

Ich bin sehr froh, dieses Buch in der Siegener Reihe veröffentlichen zu können, zumal jeder Leser inzwischen weiß, dass Nordmali wieder brennt. Wenn auch dieser erneute Kleinkrieg nicht aus den Erwartungen herausfiel, vor allem nach der Lektüre dieses Buches, war der schnelle Vorstoß eines Teils der Tuaregrebellen und Araber, der von den Franzosen gestoppt wurde, doch überraschend für mich.

Unvorhersehbarkeit bestimmt stets den Ausbruch der Kleinkriege. Auch Georg Klute wurde von den Rebellionen der Tuareg überrascht, was umso mehr sein wissenschaftliches Interesse weckte. Dieses Buch ist wunderbar klar und spannend geschrieben, und ich wünsche ihm eine große Leserschaft.

Trutz von Trotha, in May 2013

********************************************************************************************************

Under these links you will find the reviews by Reinhart Kößler, Maarten Kossmann, Judith Scheele and Petr Skalník, publications by Georg Klute, text collections and studybooks of North and West African Tuareg varieties and a festschrift on the occasion of Klute’s retirement from the University of Bayreuth in 2018:

Während der vergangenen Jahrzehnte haben Aufstände von Tuareg, aber auch Entführungen und zuletzt der Krieg und die französische Intervention Anfang 2012 immer wieder für kurze Zeit die Aufmerksamkeit auf den Norden von Mali und Niger sowie den Süden Algeriens gelenkt. Georg Klute hat diese teils überraschenden und stürmischen Entwicklungen seit dem Beginn des Aufstandes in Mali 1990 intensiv erforscht. Nicht zuletzt aufgrund seiner ungewöhnlichen Kontakte zu wichtigen Akteuren und seiner intimen und langjährigen Kenntnis der Region ist aus diesen Arbeiten eine im besten Sinne „dichte Beschreibung“ des Aufstandes der 1990er Jahre, seiner Hintergründe und Folgen entstanden. [...]

Insgesamt erscheint es kaum möglich, diesem faszinierenden Buch in einer Rezension gerecht zu werden. Es fordert – fördert aber auch – die Bereitschaft, sich einsaugen zu lassen und dem Autor auch in die Arabesken etymologischer Darlegungen und biographischer Details von manchmal mythologischen Personen sowie einer manchmal in die Zeit der islamischen Eroberung Nordafrikas zurückreichenden longue durée zu folgen.

Reinhart Kößler in Peripherie, 134/135, 371-373

The book divides into four parts that cover the main aspects of Klute's research interests over the years: the poetry of rebellion; exile; desert war; and regional structures and concepts of power (Herrschaft). All four tell the same story – that of the genesis, development and aftermath of rebellion in northern Mali in the 1990s – from different, but mostly internal, perspectives, thus providing a detailed picture of the socio-cultural background and motivations of Malian rebels. Comparative material is drawn from northern Niger and southern Algeria. At 170 pages, the first section is the longest. It is based on a collection of Tuareg songs dating from 1978 to the mid-1990s, which are analysed in detail and with great linguistic sensibility, thereby making much original material accessible here for the first time to European readers. The second part, ‘Exile’, provides an internal view of emigration and return, by drawing parallels with older patterns of Tuareg mobility. In this section, Klute touches on trans-border trade and smuggling, thereby providing a much-needed reminder of the historicity and banality of many of the networks that are today often decried as ‘criminal’ or even ‘Islamist’. He also details the importance of regional connections, in particular with Libya, in preparations for the 1991 rebellion. Part 3, on desert war, provides an in-depth account of the practicalities of rebel warfare in northern Mali; to my knowledge, this is unique in its approach and detail, although the strategic slant adopted feels at times uncomfortably close to international security concerns. Part 4 investigates local notions of power, tracing the career of the Ifoghas group in the Malian Adar from colonial times to the present. Although the colonial history of the area is relatively well known (and, indeed, the author seems to draw on relatively limited primary sources), the second half of this section is concerned with the contemporary situation, in particular with regard to how the traditional leading families in the area have succeeded in increasing their power through and after the rebellion. This last section provides fascinating insights into a little-known topic, and constitutes, to my mind, the most coherent and convincing interpretation of recent political dynamics in the Kidal region that has appeared to date. Overall, the book provides an extremely rich and well-researched account of socio-cultural and economic developments in northern Mali, from the late 1970s onwards. Based on a mixture of internal documentation, innumerable interviews and very long-term participant observation, it is the most complete analysis of events in the Kidal region – and of recent ‘Tuareg rebellions’ more generally – that exists.

Judith Scheele in Africa – The Journal of the International Africa Institute, Vol. 85/1, 2015, 165-167

Summarizing, this is a very satisfying book, well-written and extremely erudite. It is a must-read for anybody who is interested in Tuareg culture, the recent history of the Sahel, or modern poetry, or who is just an amateur of the music of Tinariwen.

Maarten Kossmann in Journal of African Languages and Linguistics, 36/2, 2015, 287-289

This monumental work has been slightly revised ‘habilitation’ thesis which has waited for publication for quite few years. The Köppe publishing house has undertaken the task of making it accessible to the academic world and the wider public. I must say from the outset that it was the right decision because the quality of the text is outstanding. [...] The book is divided into four major parts. Beside the theoretical and methodological Introduction, the author begins with the poetry of the revolt which he collected in cooperation with local Tuareg specialists. This 180 pages long treatise is as very suitable introduction as it is an original approach to the Tuareg uprising. But let us first look at the introduction. Its central part – political anthropology of Tuareg rebellions – asserts among it. It brings the rather intractable subject of war into the centre of interest not only for anthropologists but also for political scientists, sociologists and historians. It deals with the African regional war but should be studied by all who are interested in the emancipation movements in other parts of the world.

Petr Skalník in Modern Africa, 1/2, 2013, 1-2

© 2026 by Rüdiger Köppe Verlag – www.koeppe.de