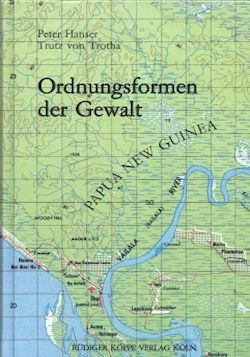

Whereas nowadays the police, public prosecution and public court system are common to almost every legal system world wide, the workings of lower legal institutions and the dispension of law in villages and small provincial towns is scarcely known. To remedy the situation, Trutz von Trotha and Peter Hanser have studied the conditions, workings and effects of the legal system of Papua New Guinea.

The authors were interested in the interaction between the formal institutions of the national legal system and the conditions in the localities, especially the flexibility of legal order in the hands of the local representatives of the legal institutions at the periphery. The focus is on the experiences and points of view of simple village police members, itinerant prosecutors and judges, who sweat in musty bureaus to prepare for sessions dealing, e.g., with the issue of a bride price which was never paid and where it is clear that the promised bride price could never have been paid.

In Ihu, the field study area of the present study, conflict and competition determine the relationships between public administration, traditional and neo-traditional institutions of mediation, and among the neo-traditional institutions themselves. At the time of the field study the conflicts between administration, village judges and village councils were exemplary. The strength and intensity of these conflicts are the result of the dynamics of a big men order. The differential structure of these conflicts points at a continuing heterogeneous order of relationship between politics and law. It corresponds to the local structures and processes about power, status and influence, where the big men are the dominant actors.

Review in “Portal für Politikwissenschaft”

Wolfgang Knöbl in Soziologische Revue, 27/2004, 193-195

Das Buch stellt eine sehr anregende Verbindung zwischen Ethnologie und Rechtssoziologie her. Es basiert auf umfangreichen Feldforschungen über Mechanismen der Konfliktaustragung in einer Region Papua-Neuguineas, die sich – fern der formalisierten Prozeduren von Rechtsstaatlichkeit – an den „Grenzen des Staates” befindet (19). Das postkoloniale Papua-Neuguinea ist für die Frage nach der Entstehung von Recht ein lehrreicher Fall, weil hier eine ausgeprägte Kultur gewaltsamer Selbsthilfe und neotraditionaler Streitregelungspraktiken von rechtsstaatlichen und parlamentarischen Institutionen eingerahmt werden. Der eigentlichen Feldstudie (Teil II) ist eine kritische Diskussion rechtsethnologischer Positionen vorangestellt, namentlich jener Auffassungen („negativer Evolutionismus”), die die universelle Durchsetzung staatlicher Rechtsordnungen als Verallgemeinerung administrativer Repression interpretieren. Für Politikwissenschaftler dürfte indes der dritte Teil, der sich mit der Zukunft des staatlichen Gewaltmonopols befasst, noch interessanter sein. Ausgehend von vier Ordnungsformen der Gewalt, entwirft von Trotha, der diesen Abschnitt weitgehend verfasst hat, das skeptische Szenario eines „undramatischen” Zerfalls moderner Staatlichkeit. Im Zuge einer um sich greifenden Privatisierung werde in den liberalen westlichen Demokratien das wohlfahrtsstaatlich abgesicherte Gewaltmonopol von einer präventiven Sicherheitsordnung abgelöst, einem „Gefüge von zunehmend eigenständigen und unabhängigen Regierungen jenseits des Zentrums und außerhalb des öffentlichen Bereichs” (352).

Thomas Mirbach in Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft, 1/2004, 270-271

Susanne Krasmann in Krim. Journal, 36/1, 2004, 73-75

Hermann J. Hiery in Jahrbuch für Europäische Überseegeschichte, 8/2008, 435-439

© 2026 by Rüdiger Köppe Verlag – www.koeppe.de