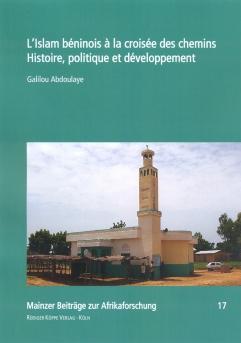

The studies available on Islam in West Africa focus on the states of the Savannah and Sahel belt, i.e. in particular Niger, Burkina Faso, Mali, Senegal and Northern Nigeria. Very few empirical studies have been carried out on Islam in the coastal states of West Africa, such as Ivory Coast, Ghana and Togo, as these countries are generally perceived as being dominated by local African religions or as Christian. Thus, the fact that the northern areas of these countries have been undergoing a rapid process of Islamization for decades is frequently overlooked. Particular deficits have existed hitherto with respect to research on Islam in Benin (formerly Dahomey).

Thus, the present study fills a major empirical gap in the research. The focus of its analysis is a series of medium-sized towns in Northern Benin (in particular Djougou, Parakou and Malanville) and the political capital Porto Novo in the south of the country, whose population has included a sizeable number of Muslims since the 19th century (demonstrating en passant that Islam in Benin is not an exclusively northern phenomenon).

The development of Islam in Benin is embedded in more comprehensive societal dynamics and is associated in particular with the development of the education system, the dynamics of the labour market and the transformation of local elites. This provides the context for the rapid differentiation of the “Islamic field” in Benin.

The author demonstrates just how productive an analysis of contemporary Islam based on the perspective of the sociology of conflict and using the methods of social anthropology can be by identifying and demonstrating the heterogeneity and poly-centrism of the “Islamic field”. Emic notions of the “Islamic community” (umma) and the purely text-oriented studies tend to conceal this propensity for conflict. Thus, this book deserves to attract the attention not only of anthropology, but also of Islamic studies and it will be particularly interesting to observe the reaction this study triggers in the very social field it examines.

In our programme further monographs and paper collections have been published on the topic Islam in Africa and languages and cultures of Benin, see these links:

© 2026 by Rüdiger Köppe Verlag – www.koeppe.de